Ann Hersey

We owe much of our understanding of our world to the legacies of those who came before us. The histories that they laid in the past, shape our present. As such, it is important to consider the mediums through which history is passed down to us. History is not simply confined to books and maps but also given to us through the things our predecessors left behind. Letters, photographs, stories, and in the case of Ann Hersey, paintings. Ann Hersey — born Ann Muller, was born at Guelph General Hospital on the 16th of July in 1953, to Doreen and Harold Muller. The eldest of what would become three children, Ann had, in most respects, a childhood that was standard of most children growing up in Southern Ontario during the second half of the 20th century. She recalls time spent in school, reading Anne of Green Gables, swimming with her friends at Riverside Park, and going on camping trips with her family. While most of us can say that we’ve had similar experiences, what stands out most clearly in Ann’s mind, are the wonderful paintings her father would create, capturing the natural beauty of our nation. ■ Jump to the full interview

|

Harold Muller began creating art from a very early age. While it is uncertain what prompted him to take up the paintbrush in the first place, Harold drew inspiration for his creations from the world around him. Art in the 20th century was very dynamic. Perturbations during the previous century had already sown the seeds for a new world order, which began the work of asserting itself in the early years of the 1900s.[1] Essentially art around the world, Canada included, was the product of the Avant-Garde movement, which focused on transgression.

This style would ultimately give birth to the modernism of the ’70s and ’80s. However, At the beginning of the 20th century, much of Canada was still wilderness, and while many Canadian artists visited Europe, the center of the art world at the time, just as many came from around the world to seek such inspiration from the natural beauty of Canada’s unmolested woodlands, and impressive mountains and rivers.[2] Harold Muller was one such artist, However, he was lucky enough to have the privilege of being born in Canada. |

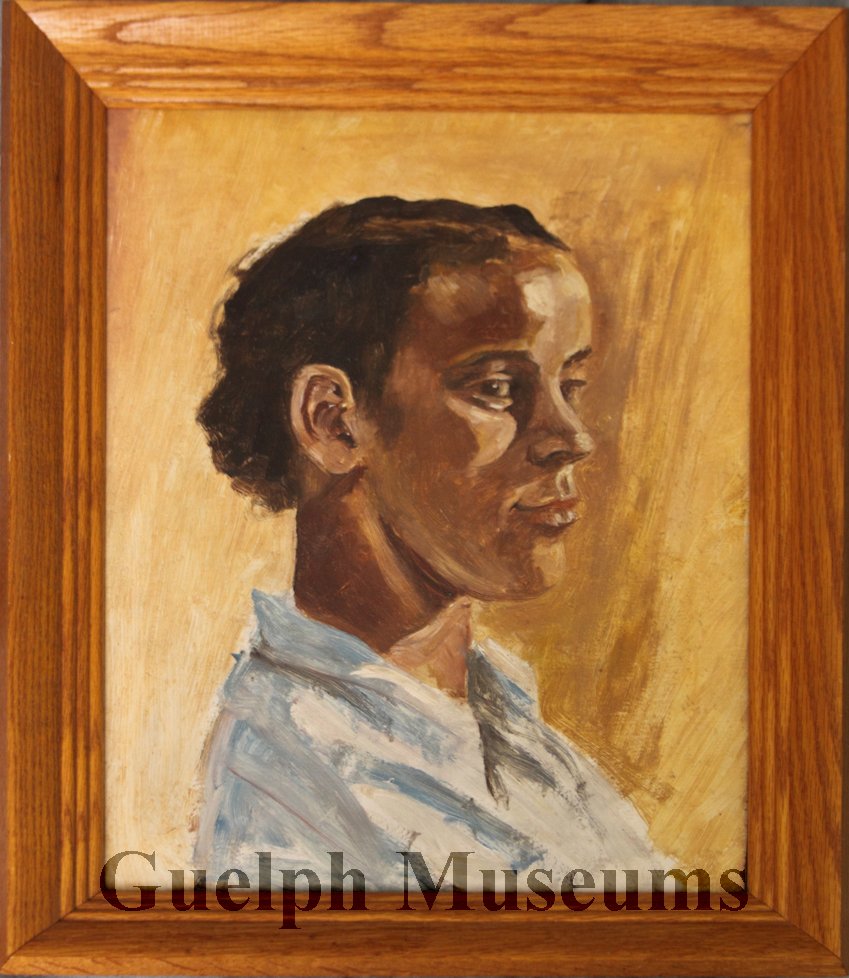

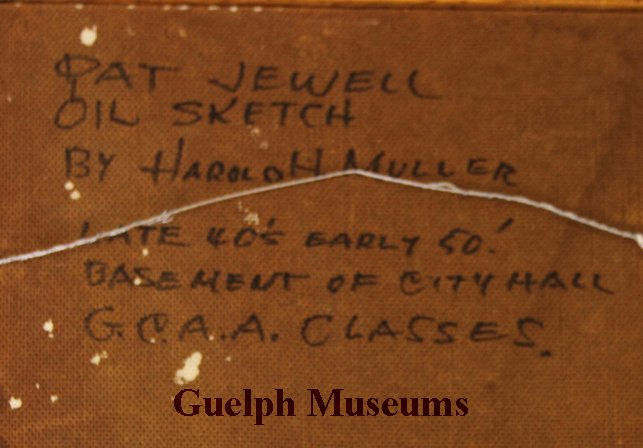

Many young artists went overseas, if they had the means, to learn their craft at one of Europe’s many art schools, however, Harold learned his craft at the Canadian College of the Arts in Toronto.[3] Here he would have learned the popular style of the time which was “Tonalism”. Marked by soft colors, and popular for depicting landscapes, the influence is obvious in several of Harold’s own paintings (See Figure 1). Canada was rapidly becoming more industrialized, and urban centers were expanding, a sentiment expressed by Ann in reflecting on how the city has changed in her lifetime:

“Guelph was always a small town — Oh, and it’s really expanded and everything — new people and different [businesses].”

|

The fact that Tonalism (see Figure 1), a style that valued subtly and harmony, rather than mathematical practicality, existed at the time, would imply a certain nostalgia.[4] That is to say that it spoke to a desire to see more traditional works, rather than more modern Avant-Garde ones. While it is impossible to know for sure what feelings and reactions Harold was hoping to inspire in others with his work, we do know that his foremost inspiration was the natural beauty of the country. This adoration led him, and his family from coast to coast across the country, in search of new vistas that captured him, and that he, in turn, would capture on the canvas. |

In reality, there were generations of Canadians who had yet to experience the ephemeral beauty inherent to the Canadian North, but due to the work of artists like Harold, such vistas become commonplace in the minds of southern Canadians.[5] While such art was accepted by some of the general population, the international art scene was slow to accept what would become synonymous with the phrase “Art in Canada”. The first great surge of inherently Canadian painting came with the Group of Seven, who rejoiced in their “discovery of the land”.[6] However, their work was rejected on the basis that it didn’t conform to popular and traditional artistic rules and that it wasn’t truthful to the content they were depicting. There was a condemnation at first of those artists who took what some might have considered too much pride in being Canadian in the Canadian outdoors. Those who took to the wilderness to do their painting as opposed to contemplating technique within their studios were frowned upon by critics and patriots alike, who deemed such artworks as little more than posters, and not even ones that would benefit the nation.[7]

Furthermore, as was discussed above, there was a call for “social consciousness” in artwork at the time, and people were concerned that such artwork left out man and the industrial scene. And while the Group of Seven endured such ridicule, no less than three decades after their disbandment, their work has been placed in history as the forerunners of Canadian art. As Malcolm Ross states in his work, The Arts in Canada: A Stock-taking at Mid-Century: “A new kind of nationalism which would celebrate, not the land but the men in it, the power lines, rather than the pines, the dams rather than the rivers, has not taken shape in our painting."[8]

Harold was a part of this generation of Canadian painters; those who saw the land for what it was and captured it for the world to experience. Travel was expensive, however, and with a wife and three children, Harold committed himself to work within Guelph, making a name for himself as a bricklayer, and as an autobody mechanic. Harold was good with his hands, and an artist through and through, as he loved working on cars and with metal, as much as he did on the canvas. Creating beautiful vehicles, was just the beginning however, as he also created a series of metal sculptures. These sculptures decorated the backyard of the Muller household, and Ann recalls them fondly, comparing the home itself to an art gallery:

“When I was young, [there were] paintings on the walls all the time, and then in the back, sculptures, some really weird sculptures!”

Ann also recalls her father’s work with wood, as well as metal, and fondly relates the story of Tiny, a small blue sailboat refurbished by Harold for his family. It is obvious that for Harold, art was always about the passion for him, rather than commercially driven:

“He wasn’t really good selling paintings so much, you know? We had so, so, so, so many paintings and my brother Kim tried to get portraits and stuff you know, but, just so, so many paintings at the house.”

Ann makes it clear that family was Harold’s top priority, even going so far as to refer to her parents as “super-parents”. The art scene in Southern Ontario during the ’60s, ’70s and ’80s was a hotbed of expression and exploration, with new mediums and styles being periodically discovered, popularized, and then replaced by one another as time went on.[9] While Avant-Garde artwork became more popular, along with new innovations in the use of film and multi-media devices to transmit new kinds of art to larger audiences, Harold contented himself to spending time with his family. Traveling across the country and expressing the things that moved him in the best way he knew how, and much to the delight of friends and relatives.

|

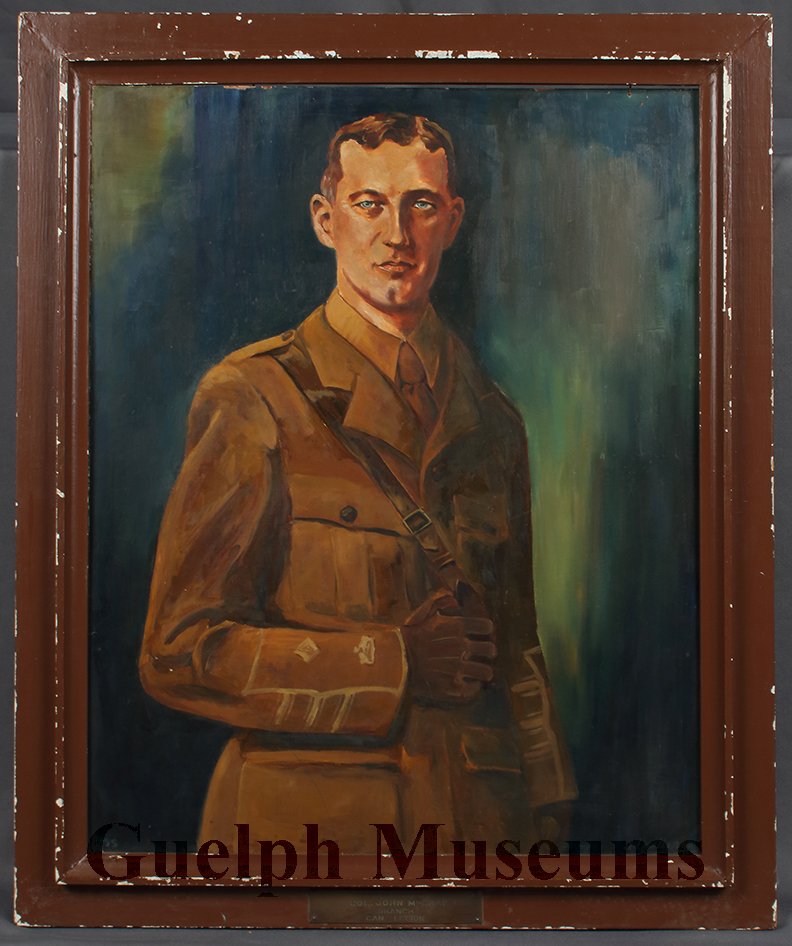

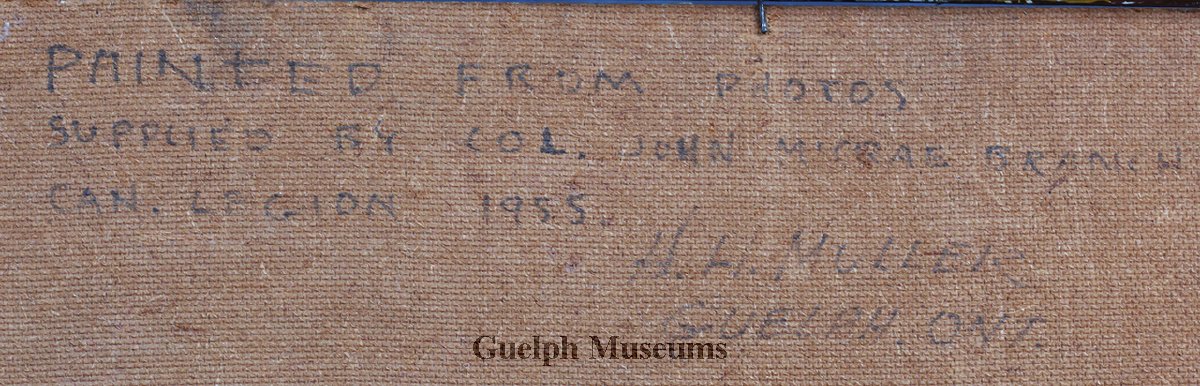

The 1960s to 1990s were a period of global uncertainty as the economy struggled to recover from the world wars. Add to this the pressures of conflicts in Vietnam and the fear of atomic warfare, many people in North America, and not just the United States were facing an uncertain future.[10] While Canada was not at the heart of many of these events, their impact was felt globally and inspired the work of many artists, including Canadian ones. Born in 1921, Harold was witness to these transformative events and would have experienced firsthand their reception in Canada. That being said, Harold didn’t seem to take much of an interest in international affairs. Many artists from the period depicted the horrors of war and expressed societal frustrations with the government and foreign policy, becoming more comfortable with the new ways in which the mediums of the period allowed them to make statements about the way things were. While other artists busied themselves, immersed in this new aforementioned culture of transgression, Harold continued to depict the scenes of everyday life. Depicting scenes from his community, and even the pool where his children practiced their swimming skills (see Figure 2). |

|

As Ann grew into a woman and eventually met her husband Brian, Harold put his talents to work fashioning fine jewelry and gifting it to her (see Figure 3). As time went on Harold demonstrated the scope of his artistic abilities by working with other mediums. Ann states: “He painted with acrylic, and then later with watercolor, and sometimes just plain chalk.” Ann goes on to discuss the other works her father did, such as creating a silver goblet for the church, along with stained glass windows, which can still be seen at the First Baptist Church today.

While history remembers Harold’s depictions of the northern forests and local features, no account of such a remarkable man’s life would be complete without mention of his altruistic, and generous spirit. In 2006, Muller unveiled a stone monument at Riverside Park, commemorating the United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child.[11] Riverside Park was the very same park where Ann spent so many joy-filled days as a child herself. The monument itself was the idea of a family friend, a 10-year-old girl with a remarkably perceptive mind.

The United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child was the first universal treaty dedicated solely to the protection of children’s rights.[12] The monument itself consists of three large pillars, depicting both children and soldiers, accompanied by smaller stones from across the country. It is a beautiful exhibit of Canadian national spirit as a world leader in social justice, as well as Guelph's support of the rights of those who are vulnerable. |

Figure 3: A photograph of silver and green agate necklace crafted for Ann by her father. |

Muller's contribution to history is experienced by many. Anyone who sits in admiration of the beauty of the stained-glass windows he worked on, or in contemplation on his monument at Riverside Park, is bearing witness to his legacy. Ultimately, however, Harold is remembered by his family. By Ann, and her siblings, and her children, and as an artist, yes, but also as a super-father. The man who refurbished sail boats, took his family on camping trips, and made beautiful jewellery for his daughter. We owe much of our understanding of the world to those who came before us. The histories that they laid in the past, shape our present, and it is Harold’s history that is one of the many which helped to shape this community, this country, and the legacy his daughter now has to share herself.

You can listen to the full interview with Ann Hersey here.

Click here to read the interviewer, Shyler Hendrickson's page and reflection on this interview.

Gallery

Other examples of Harold Muller's art, and life works. Click on any image to enlarge.

|

|

|

|

Endnotes

[1] Dudek, Stéphanie. “Written in Blood: 20th Century Art.” Canadian Psychology 30, no. 3 (1989): 105-116. https://www-proquest-com.subzero.lib.uoguelph.ca/scholarly-journals/written-blood-20th-century-art/docview/1297763632/se-2?accountid=11233.

[2] Murray, Joan. Canadian Art in the Twentieth Century. Toronto: Dundurn Press. 1999, p. 11. http://search.ebscohost.com.subzero.lib.uoguelph.ca/login.aspx?direct=true&db=e000xna&AN=244765&site=ehost-live&scope=site&ebv=EB&ppid=pp_Cover.

[3] Murray, "Canadian Art in the Twentieth Century," 11.

[4] Murray, "Canadian Art in the Twentieth Century," 12.

[5] Ross, Malcolm. The arts in Canada; a stock-taking at mid-century. Toronto: Macmillan. 1959, p. 9.

[6] Ross, "The Arts in Canada," 11.

[7] Ross, "The Arts in Canada," 11.

[8] Ross, "The Arts in Canada," 11.

[9] Arnold, Grant and Karen Henry. Traffic: Conceptual Art in Canada, 1965-1980. Edmonton: Art Gallery of Alberta. 2012, 59-60.

[10] Findley, Carter V. Twentieth-century world. Belmont: Wadsworth Cengage Learning. 2011, 281.

[11] O’Flanagan, Rob. “Muller equally adept at patching cars and creating art.” at Guelph Mercury. March 10, 2015. https://www.guelphmercury.com/news-story/5470024-muller-equally-adept-at-patching-cars-and-creating-art/.

[12] Fottrell, Deirdre. Revisiting Children’s Rights: 10 years of the UN Convention on the Rights of the Child. Netherlands: Brill Publishers. 2001, 1.

___Gallery.jpg)